Snowshoe Thompson is the most famous skier to come out the California gold rush days. Here's a look at his fascinating life.

.Article Links: Main Article | Credits | Citations & References | Other Resources

_____________

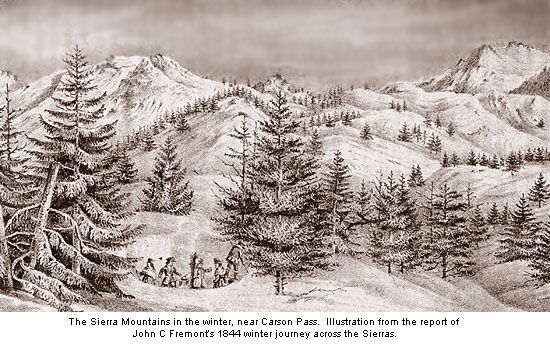

It is early winter, 1855. In Placerville on the west slope of California's Sierras, the prospects for any kind of reliable mail service over the mountains are bleak.

The prospects are even bleaker for the settlers living on the east slope of the Sierras in Carson Valley (south of present day Carson City, Nevada). At least, Placerville can get news from Sacramento, only 50 miles to the west, and San Francisco beyond that. Carson Valley, however, is without any means of communication over the Sierras and is virtually cut-off from the world. The residents of Carson Valley might as well be living on an island in the middle of the ocean.

It is all because of the Sierras' snow. It grows to extraordinary depths, far beyond the experience and imagination of anyone who had come to California since gold was discovered in 1848. Cabins—parts of towns even—drift over and disappear under the great layers of snow. The snow builds to such depths that not even stove pipes are left.

The smart ones have boarded up their cabins, braced ceiling rafters, and have gotten out before winter. They knew that snow would bring travel to a virtual standstill. Those who wait too long to get out will end up wallowing in snow, and if they manage to make it back to the valley alive—and with all their toes and fingers intact—they'll have plenty of harrowing tales of survival to tell.

About the only ones who travel in the Sierras on purpose in the winter are the mail contractors. That's their job. In the summer, it's challenging work, but, in the winter, it's downright backbreaking. To get through, they've attempted different routes through the mountains and experimented with various traveling methods. One mail contractor even resorted to using wooden mauls, beating and packing the snow, so his pack animals would have something firm to walk on. This they did mile after mile. When they got to Carson Valley they were spent. More recent attempts had been made on webs or Canadian snowshoes, with the mail carried on men's backs. But even those were not reliable. Just that December, a man by the name of Bishop took 8 days to get across the Sierras and was "badly frozen" in the process.

That's the way things stood in 1855. Mail service over the Sierras in the winter was simply uncertain. Things, indeed, looked bleak.

Then, a strapping young Norwegian immigrant appeared on the scene.

Within a short time, this young, blond Norseman would be celebrated throughout the Sierras — and become one of the most famous cross-country skiers of all time. His reputation and legend would grow by leaps, and, in time, the facts and fiction of his life would become so intermixed that it would become difficult, if not impossible, by modern historians to separate the two.

This much we do know: his name was John A. Thompson. To the admiring residents of the Sierras, however, he was known simply as Snowshoe Thompson.

John Thompson immigrated with his family from Norway when he was 10 years old. In 1851, at the age of 24, Thompson arrived in California. It was just 3 years after gold had been discovered, and the mountains were crawling with recent arrivals. Prospectors had spread out all over the Sierras and more strikes were being made, particularly in a lovely region of the Sierras to the west of Lake Tahoe. It was here in a swath of mountainous country between Sacramento and Reno—60 miles to the north and south of present day Interstate 80—that Thompson would make his mark.

This area of high peaks and preternaturally abundant snow is sometimes referred to as the Lost Sierra for its long-gone boom towns. But it abounds with much more than mining history. This is also a place where skiing history was made. Indeed, it is hallowed ground, for the Lost Sierra is the cradle of skiing in North America.

Here skis first made their appearance in great enough numbers to establish a toe hold in the New World. According to ski historian William Berry, it began with a few isolated individuals in the early 1850's. While who and when skis were first used remains murky, it is clear that by the tail end of 1850's, they were beginning to proliferate throughout the area. And by the 1860's in the Lost Sierra, they had become de rigueur.

Thompson played an important role in the popularization of skiing in the Sierras. While he probably wasn't the first, he was certainly among the earliest skiers and quickly became the most well known. His deeds and exploits were so widely reported that, in essence, he became the sport's poster child. Television producers, had there been television in those days, would have loved him.

He would have also caught the eyes of the ladies—what few of them were around. He was, to use a more contemporary term, something of a hottie. That, according to Dan DeQuille of the Territorial Enterprise who interviewed Thompson. (DeQuille, incidently, gave a young Samuel Clemens—Mark Twain—his first newspaper job, and certainly must have had a talent for sizing up one's character.) John Thompson, DeQuille wrote, was a "man of splendid physique. His features were large, but regular and handsome. He had the blond hair and beard, and fair skin and blue eyes of his Scandinavian ancestors."

He would have also caught the eyes of the ladies—what few of them were around. He was, to use a more contemporary term, something of a hottie. That, according to Dan DeQuille of the Territorial Enterprise who interviewed Thompson. (DeQuille, incidently, gave a young Samuel Clemens—Mark Twain—his first newspaper job, and certainly must have had a talent for sizing up one's character.) John Thompson, DeQuille wrote, was a "man of splendid physique. His features were large, but regular and handsome. He had the blond hair and beard, and fair skin and blue eyes of his Scandinavian ancestors."

The striking, blue-eyed Thompson had dabbled at mining in Placerville and farming near Sacramento, but, like many in those days, he was always on the look-out for other employment opportunities. Too, he had the constitution and inclinations of his Viking heritage, and a job with an adventurous slant would undoubtedly pique his interest. According to some writers, it was an ad in the Sacramento Union in 1855 that led him to the profession which would open to the door to fame: "People Lost to the World; Uncle Sam Needs a Mail Carrier"

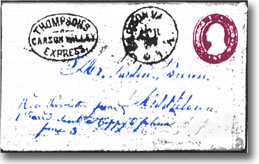

The mail route referred to in the Union's ad was between Placerville, 50 miles to the east of Sacramento, to Mormon Station, 25 miles southwest to Carson City, Nevada. (Mormon Station located in the Carson River valley would eventually be renamed Genoa, Nevada.) The total distance of the route: 90 miles, all the way, from one side of the Sierras to the other.

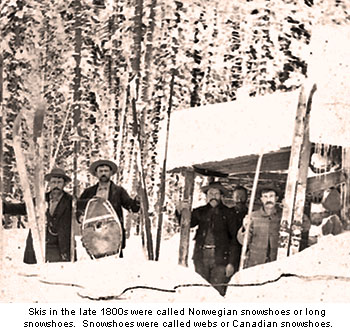

Thompson got the job. His first run would be in early January, and for it, he planned to use skis, a method of winter travel he had learned as a boy in Norway. The term "skis," however, had not come into usage yet. They were called "Norwegian Skates" by the Sacramento Union. Two other common names used by newspapers of that era included "Long Snowshoes" and "Norwegian Snowshoes." What we now know as snowshoes were called "webs," "Indian Snowshoes" or "Canadian Snowshoes."

Relying on his boyhood memory, Thompson constructed his first set of Norwegian skates out of a freshly cut—and very green—oak plank. As you can imagine, they were monstrosities. According to De Quille, Thompson weighed them when he got to Placeville and they tipped the scales at 25 pounds. He eventually got the weight down on subsequent pairs, but, even so, the skis of the 1800's were still formidable in size.

In a newspaper article some years later, Thompson described the dimensions of his skis: 9 feet long, 4 inches wide at the tip and narrowing to 3 1/2 inches. Thickness: 1 1/2 inches.

Since Norwegian skates were still relatively unknown, and still unproven, there were lots of doubters in Placerville. Bishop's recent ill-fated, 8-day trip across the Sierras was a case in point. Even Thompson's friends in Placerville, De Quille tells us, urged him not to do it. They were afraid that the unwieldy long boards strapped to his feet would be unmanageable—and that he would "dash his brains out against a tree" or fly off a cliff.

Since Norwegian skates were still relatively unknown, and still unproven, there were lots of doubters in Placerville. Bishop's recent ill-fated, 8-day trip across the Sierras was a case in point. Even Thompson's friends in Placerville, De Quille tells us, urged him not to do it. They were afraid that the unwieldy long boards strapped to his feet would be unmanageable—and that he would "dash his brains out against a tree" or fly off a cliff.

Thompson, however, had hedged his bets and had practiced with his skis in the high country above Placerville prior to his first trip. By the time his first trip came around, he was ready and confident enough of his skills. On January 3, 1855, he left the settlement behind and disappeared into the mountains.

Then there was silence.

A short while later, he was back. Jaws dropped open. Friends shouted hurrahs. He had done it! And far faster than anyone imagined. When he later arrived at Sacramento, his total return time from Carson Valley was an amazing three and half days. He had cut almost five days off Bishop's time and wasn't any worse for the wear. The naysayers were silenced. Snowshoe Thompson, a moniker that he would pick up over the next few years, had proven that skis were an efficient and suitable mode of winter transportation in the mountains.

The Sacramento Union announced that first famous trip: "Mr. John A. Thompson left Carson Valley on Tuesday morning and reached this city at noon yesterday. He was three days and a half in coming through from Carson Valley and used on the snow the Norwegian skates, which are manufactured of wood."

The following month, the Union was warming up to this man Thompson, calling him an "adventurous and hardy mountain expressman." He regularly made the journey twice a month through the rest of the winter. His reliability, kindness and physical prowess quickly earned the admiration and respect of the Sierra residents. The seeds had been planted. The roots firmly established. A legend was about to spring forth from the Sierra soil.

His pack, weighing from 60 to 80 pounds, included mail, newspapers, periodicals, ore samples, and medicines. UPS and FedEx can't claim any originality when it comes to express service plans. Thompson long beat them to it, instituting 2-day and 3-day service. He could run the 90-mile Placerville to Carson Valley leg in 3 days and reverse journey in 2 days.

Not all of the distance was done on skis. The snow line varied depending on the month and severity of the winter. Skis, however, were needed in 1856 and were what got him swiftly across the high, snowbound portion of the route.

He was back at it the following winter. The Sacramento Union reported that during the winter of 1856-1857, most of his 31 crossings of the Sierras were on skis. That second winter appears to be the high water mark in Thompson's trans-Sierra ski express. In 1858, he was again carrying the mail, but with improved wagon roads, he was now using horse-drawn sleighs. He continued, however, to use skis when the roads could not be broken. For the next two decades of his life, he used Norwegian skates on and off for other shorter mail routes and for privately contracted express service.

* * *

Amazingly, Snowshoe Thompson carried little in the way of bedding and clothing with him. His weighty skis and pack—and moderate Sierra winter temperatures—might have had something to do with it. Still, it's remarkable that his only indulgence to comfort was a wide rimmed hat and Mackinaw. He kept warm during the day by the exercise of skiing. At nights, he built a large fire, lay on a bed of pine boughs and used his mail sack for a pillow. He would stretch "himself upon this fragrant couch," wrote Hubert Howe Bancroft, a west coast historian, "and with his feet to the blaze and his face to the stars slept soundly and safely."

Meals on the trail consisted of dried beef and sausage, crackers and biscuits. He didn't know about waxing. And when freshly fallen snow would warm, it would stick to his skis in great clumps. When that happened, he'd stop and wait for evening when the snow pack would glaze over and he could glide once again without the encumbrance of wet, sticky snow.

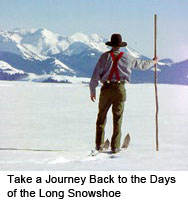

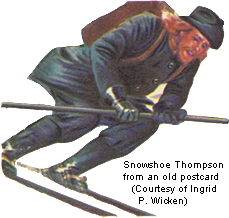

To propel himself forward on the flat and to climb hills, he used one long pole. Two poles came much later. The pole, sometimes called a "balancing pole," was also used to assist him on downhill runs. Apparently, Thompson was a master in its use. "He flew down the mountainside," Dan DeQuille wrote, describing his graceful manner. "He did not ride astride his pole or drag it to one side as was the practice of other snow-shoers, but held it horizontally before him after the manner of tightrope walker. His appearance was graceful, swaying his balance pole to one side and the other in the manner that soaring eagle dips its wings."

To propel himself forward on the flat and to climb hills, he used one long pole. Two poles came much later. The pole, sometimes called a "balancing pole," was also used to assist him on downhill runs. Apparently, Thompson was a master in its use. "He flew down the mountainside," Dan DeQuille wrote, describing his graceful manner. "He did not ride astride his pole or drag it to one side as was the practice of other snow-shoers, but held it horizontally before him after the manner of tightrope walker. His appearance was graceful, swaying his balance pole to one side and the other in the manner that soaring eagle dips its wings."

Snowshoe Thompson—the man who could ski like a soaring eagle—was also known for his generosity and for his willingness to come to the aid of others. An incident early in his second year of carrying mail over the Sierras helped establish that reputation. On December 23, 1856, Thompson stopped by a cabin along his route, and found James Sisson lying on the floor, barely alive. Several days prior, Sisson had been caught in a storm and had frozen his feet. He eventually reached the cabin where Thompson found him. Thompson made the man as comfortable as possible and skied out the next day to Carson Valley. He convinced five others to go back with him, outfitting each of the rescuers in skis. Once back at the cabin, they fashioned a sled and eventually got the ailing man back to the valley by the 28th.

The story doesn't end there. In order to save the man's life, Sisson's gangrenous legs would have to be amputated, but the doctor treating him was unwilling to undertake the operation without an anesthetic. Thompson, who must have been thoroughly knackered after the rescue, volunteered to make another trip. He again put on his skis and made the 90 mile trek to Placerville. Then traveled 50 more miles to Sacramento. There he obtained the anesthetic, turned back around and did it all over again, retracing his path back to Carson Valley. Sisson, reportedly, recovered and eventually moved back to the east.

"Most remarkable man I ever knew, that Snowshoe Thompson," said Postmaster S. A. Kinsey. "He must be made of iron. Besides, he never thinks of himself, but he'd give his last breath for anyone else - even a total stranger."

"Most remarkable man I ever knew, that Snowshoe Thompson," said Postmaster S. A. Kinsey. "He must be made of iron. Besides, he never thinks of himself, but he'd give his last breath for anyone else - even a total stranger."

He might have been a bit too generous. Despite the incredible physical effort he put into providing reliable mail service, he was never ever fully compensated for his work. With the support of friends, he petitioned the Nevada legislature and the U.S. Congress, but, in the end, he never received the remuneration which he was owed. There were other life disappointments, of course. His son, and only child, died when the boy was only 11. It must have been a terrible blow to the strong Norwegian.

Life went on. De Quille describes Thompson at the age of 49 appearing in the prime of his life. "His eyes was bright as that of a hawk, his cheeks were ruddy, his frame muscular. His face had the look of repose, and he had that calmness of manner, which are the result of perfect self reliance." He was still skiing, De Quille wrote. He would load a quarter beef on his back and ski up a steep canyon to supply miners working at the Pittsburg Mine, 20 miles south of Thompson's ranch.

It seemed that even in middle age, the robust Snowshoe Thompson had many more years of skiing the mountains, but it was not to be. Shortly after the De Quille interview Thompson suddenly fell ill with a liver ailment. It was spring time, and the barley on his ranch needed to be planted. Thompson struggled out to his field. Bending over to sow the seeds was too painful, so he mounted a horse and spread the seed from bucket held out in front of him. Afterwards, unable to raise his 6 foot frame, the ever moving Norwegian was confined to his bed. Two days later he died.

It seemed that even in middle age, the robust Snowshoe Thompson had many more years of skiing the mountains, but it was not to be. Shortly after the De Quille interview Thompson suddenly fell ill with a liver ailment. It was spring time, and the barley on his ranch needed to be planted. Thompson struggled out to his field. Bending over to sow the seeds was too painful, so he mounted a horse and spread the seed from bucket held out in front of him. Afterwards, unable to raise his 6 foot frame, the ever moving Norwegian was confined to his bed. Two days later he died.

He was buried beside his son in Genoa, in Carson Valley for whose residents he had first carried the mail by snowshoes over the Sierras. Some time after his death, his wife had a tombstone placed over his grave. Carved on top of the tombstone are two crossed skis.

"To ordinary men there is something terrible in the wild winter storms that often sweep through the Sierras," wrote De Quille. But not to Snowshoe Thompson. The mountains were his sanctuary, and storms were just another part of its raw beauty. On his skis, he could freely move across the snow covered landscape. The feeling of freedom must have been never more real to Thompson than when gliding downhill, holding his balance pole out in front of him, dipping it one direction and then the other, his wide-brimmed hat flapping in the wind and the Sierras spread out in front of him. At times like that, he must have felt like a soaring eagle.

"To ordinary men there is something terrible in the wild winter storms that often sweep through the Sierras," wrote De Quille. But not to Snowshoe Thompson. The mountains were his sanctuary, and storms were just another part of its raw beauty. On his skis, he could freely move across the snow covered landscape. The feeling of freedom must have been never more real to Thompson than when gliding downhill, holding his balance pole out in front of him, dipping it one direction and then the other, his wide-brimmed hat flapping in the wind and the Sierras spread out in front of him. At times like that, he must have felt like a soaring eagle.

END

Credits | Citations & ReferencesA Great Read...

|

|

The book is truly a classic, one reviewer calling it the "standard by which other guidebooks are judged." Click here for more information on Winter Tales and Trails. . |

|

You may also enjoy Never Turn Back. It's been widely acclaimed by reviewers and readers alike. The standard book trade reference Books in Print calls it a " masterfully written book" and "one the outdoor world's finest works." The book also appears on a number of best reading lists. Click here for more information. |

|

Other ResourcesIngrid P. Wicken was kind enough to provide a scan of the Snowshoe Thompson postcard which is reproduced at the top of this page. Ingrid has written the definitive book on the history of skiing in southern California with particular emphasis on the developed ski areas. The name of her book is Pray for Snow: The History of Skiing in Southern California. More information. |

|

Credits

1. Ski historian Ingrid P. Wicken provided the scan of the Snowshoe Thompson postcard (found at the top of the article). The post card was published by Gum Products in 1956. This is the description from the back:

Adventure Snowshoe Thompson-Mailman. John A. Thompson began skiing the mail from California to snowbound miners in the Sierras in 1856, making the 90-mile round-trip in five days. Supplied Nevadans with needles, laxatives, perfumes; carried type for the first edition of the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. Challenged California clubs in cross-country races, first formal ski competitions held in world, preceding first regularly-held meets in Oslo, 1862.

2. The profile photograph of Snowshoe Thompson was provided by the El Dorado County Historical Museum. A fee was paid for its use. The date of photo is unclear. It was probably taken in the late 1860's to early 1870's—and it was likely taken in Carson City.

3. The engraving (of a skier using his balance pole located in the next near the phrase "Most remarkable man I ever knew...") is from: Marvels of the New West: A Vivid Portrayal of the Stupendous Marvels in the Vast Wonderland West of the Missouri River by William M. Thayer. Thayer's "Marvels" was published in 1890 and is in the public domain.

4. The photo of Snowshoe Thompson's Grave was taken in Genoa, a small town in Nevada to which Snowshoe carried the mail. My thanks to Keith A. Corban who provided the photo at no charge. Keith owns a bed and breakfast in Genoa and welcomes history buffs.

5. Portions of this article appeared in the January, 2005 issue of Cross Country Skier Magazine.

Citations and References

William Banks Berry, Gold, Ghosts & Skis: Lost Sierra (Soda Springs, CA: Western America SkiSport Museum, 1991), pp 11, 26, 72-82.

Kenneth Bjork, Snowshoe Thompson: Fact and Legend, Norwegian-American Studies, Vol XIV (Northfield, MN: Norwegian-American Historical Association, 1956), p 62-88.

Dan De Quille, “‘Snow-shoe Thompson,’” Overland Monthly 8 (October 1886): 419-435.