Copyright & Revisions: Copyright © 1997. Reformatted in 2013. No changes made to text.

Publication History: Originally published in the Proceedings of the 1997 Conference on Outdoor Recreation and Education (ICORE). Citation: Watters, R. (1998). Changing times in outdoor education: An essay. In Jones, R. & Wilkinson, B. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 1997 Conference on Outdoor Recreation and Education (ICORE) Adventuras En Mexico, Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan (pp. 228-230). Salt Lake, UT: The Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education.

Reproduction Information: You are welcome to provide links to this page or to use short quotations and paraphrases in other documents as long as they appropriately reference the source. There is no charge for non-profit organizations to reproduce or publish extensive parts or all of this paper, but please obtain advanced permission from Ron Watters (wattron@isu.edu). Photo credits: Ron Watters.

Abstract

Using an incident in which an Outdoor Program is blamed for promoting underaged drinking as a point of discussion, the author ruminates on the changes that have occurred in the field over the years. Because of a number of factors, the climate existing in outdoor education is far less personal than in previous years. Unless educators are aware of the changes and make adaptations to deal with such changes, the outdoor field is in danger of losing much of the spark and spirit that makes it such a rewarding endeavor for which to dedicate one's life.

As soon as I read the letter, I knew we were in trouble. The letter writer was accusing us of providing free alcohol to underaged individuals under our care.

I was looking at a copy of the letter, but originals were already on their way to two newspapers. I don't promote underaged drinking, but suddenly I found myself and those who work with me accused of doing just that. My big problem was that the letter writer was probably right. Underaged drinking had likely occurred. We just hadn't seen it.

I run the outdoor program at Idaho State University and the incident had occurred at one of our events this last fall. The university is located in the southeast Idaho town of Pocatello, a conservative area and much of the population are members of a religion which strictly forbids drinking. Idaho State has a no-nonsense school administration which is very sensitive to community values and has little tolerance when a department creates bad press, particularly bad press concerning alcohol. Indeed, I found myself in trouble.

My predicament was another, albeit dramatic, sign of changing times in the outdoor education world. For a good many years, we in the outdoor programming business at universities and other other non-profit organizations have been wrapped in a warm down comforter, insulated from the vagarities of the real world. We have been largely insulated by perceptions and images. Those who have participated in our programs in the past never thought of us as a "business" or an institution. They and we were a part of group of friends that would go on trips and learn about the outdoors.

Although, as the director of the program, I still worried about such things as budgets, liability, personnel, and other normal concerns of running a business, I still enjoyed the satisfaction of working with people who felt the part of a large family environment. It was an environment that few other working situations offer.

But that's all over now. The family went through a divorce. It wasn't an ordinary divorce, and it didn't occur quickly; rather, it happened over the span of twenty years. During that time period, the outdoor programming family just grew too big and too diverse and much of the original familial bonds dissolved as the field became mainstream.

For our distant commercial in-laws the change occurred nearly overnight. Fifth Avenue advertising campaigns made outdoor adventure the "in" thing, and the styles and varieties of outdoor clothing and gear mushroomed as new markets were created. Publications quickly followed suit. The old quirky but personable Mountain Gazette with its black and white photography was replaced by the slick, glossy Outside Magazine with expensive advertising and sardonic wit. Clients on guided trips also began to change. No longer satisfied with ordinary trips, they wanted — or they had been convinced that they wanted — adventures portrayed in films like River Wild. To stay in business, outfitters found that they needed to offer something more like Disneyland experiences than outdoor experiences.

Outdoor educators were the last to experience these changes. Part of the reason the change came so late had to do with public perception. We were always perceived as a bit different, as an odd, independent bunch doing risky things. That attracted a certain kind of person to our programs, an individual who expected a few bumps in the road and who was willing to accept pitfalls as a normal course of the adventure.

Participants in outdoor programs lived, what pundits might have described at the time, an alternative lifestyle. Their adventurous nature was looked on with awe, if a little warily, by the general public. Things like climbing, backcountry skiing, whitewater rafting were exciting from a vicarious standpoint, but they were things that normal folks just didn't do.

Mass marketing of the outdoor experience has changed all that. Outdoor adventure activities has been become everyday stuff. Even the President of the United States while on family vacations includes a whitewater trip as a normal part of the holiday agenda. Because of this now universal acceptance, we've seen tremendous increases in the numbers of participants in outdoor education programs, but we've also paid a price.

We no longer represent an alternative lifestyle. We are the mainstream lifestyle. We find ourselves being held to the same standards as other businesses. Participants expect more. They expect trips to run smoothly and there's less acceptance of personal responsibility. If something goes wrong, it is the outdoor program's fault, not the participants.

Outdoor Programming, despite its non-profit roots, is now perceived as a business, and outdoor educators are no longer thought of as friends or as part of an extended family but as something impersonal: an institution, an organization, nothing of flesh and bone.

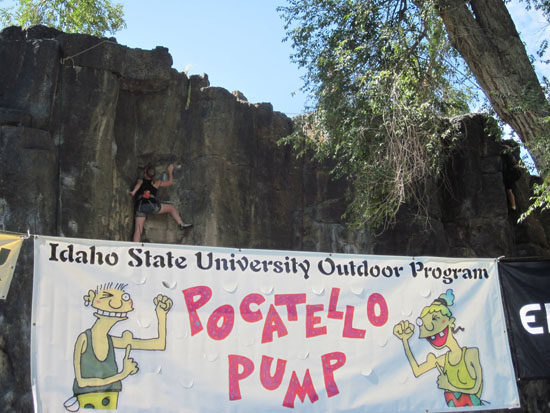

Which brings me back to the letter to the newspaper and underage drinking. The event at which the underaged drinking occurred is something called the Pocatello Pump. It's a rock climbing contest that we sponsor each year. In it's beginnings, it was a loosely organized affair. Climbers would try to climb as many routes as they could during a time interval and accumulate points. High point climbers won a few cheap prizes. Free beer was provided at a rollicking post event party, and no one really cared who had won what.

Through the years, things began to change. We solicited more expensive prizes from stores and manufacturers. We learned how to better organize and promote the event in national climbing magazines. We started attracting good climbers from different parts of the country and the level of competition went way up. One year, something happened which became an omen of things to come. A woman in one of the advanced climbing categories altered the numbers on her score card. We didn't discover the cheating until after the event and after she had gone home with several hundred dollars in prizes. What we didn't or couldn't have known at the time was that she represented an entirely new kind of competitor — and an entirely different participant in our programs.

Last year, one of the local competitors went into a temper tantrum when he couldn't make it up a climb, ripping tape off the wall which divided two climbs. He stomped around telling all who would listen how shoddily the event was run. We got through the awards ceremony, but there was a bad taste in our mouths from the affair. The local competitor was someone we all knew well and who had participated many times in outdoor program events, but seemed to have little empathy in the kind of work that went into the event.

Then about two months later, the final blow fell: the letter appeared in the town's newspaper. It had been written by one of the competitors, a young woman who had also participated in other Outdoor Program events. She complained in her letter that the free beer available at the awards ceremony had been drunk by at least one underaged individual and that she was angry at the pump officials (us) for creating an environment which led to inappropriate drinking.

The irony of the letter was that I agreed with her. The temper tantrum thrown by the male competitor could be easily brushed off as a childish display. But she had a valid point. Even though, we had been careful on the amount of beer — only one bottle was available for less than half the people attending the awards' ceremony — we had never carefully thought through the problem of an underaged individual availing themselves of a drink.

Soon after reading the letter, I contacted the letter writer and met with her. She was surprised that I would seek her out, but I wanted to listen to her and I wanted her to know that I agreed with her. I also wanted to do something else. I wanted to put a face on the program. I wanted her to know that the program was living and breathing and had a personality. When she wrote the letter she was attacking an inanimate object, an impersonal institution.

I spent the next few days meeting with university officials, but by then the whole incident had seemed to have blown over and though, personally sustaining some wounds, the program had survived.

Those of us who have been in the outdoor education field for a while probably know that deep down we'd have to give up the security of the down comforter that has insulated us from the outside. The changed outdoor world that we now live in isn't an easy one to accept. And while most of us in outdoor programming would never want do anything different for work, we still need to remind ourselves of the change and make adjustments in how we respond to it. How well we respond and in what way will determine whether we are able to save something of that old magic and family atmosphere which, though diminished, still lies at the heart of our profession.

[END]

|