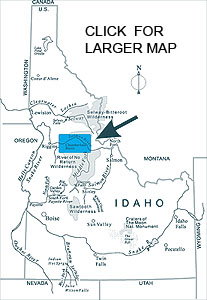

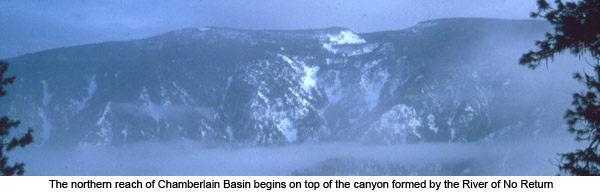

I wrote this story one warm, fall day camped along the Middle Fork of the Salmon River for a small literary journal called the Rendezvous. The theme of the issue was "in another language." When I sat down to think about it, I immediately thought of maps--and about one winter when I lost my way in the Chamberlain Basin, the high, timbered country rising above the Middle Fork, downstream from where I was camped.

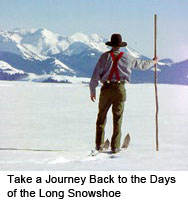

When I need a refuge, I have my art. The idea of art, however, wasn't on my mind as I climbed up the gentle incline and through the gangly forest of lodgepole pine. Earlier that day, my skis had barely made an indent in the hard, crusty surface of the snow, but now higher in elevation, I was sliding easily through a skim of loose snow, kept soft by the cooler temperatures, making miles in good time.

Yet, it is times when you are making easy miles and not thinking about art that you may end up needing it most. It's not the works of Picasso, or Monet or Munch that I speak of. Rather, it's the intricate and expansive earth-rich work of Arrowsmith, Hayden, Wheeler and Powell.

Admittedly, they are not the everyday names of the art world, but at times, I'm willing to bet that you've stopped to admire their work. You may have had no idea that they or their fellow artists were behind the work, for they often do not sign their names to their creations. They go quietly about their business and create art that we aficionados find beautiful and inspirational beyond description. We collect it, hoard it, hang it on our walls and drool over it like any other passionate collector of art. The art I'm referring to here, of course, is the art of the map.

Inevitably, there are those who would disagree and say maps aren't art, that maps are more of a paint-by-the-numbers creation than the work of inspiration. But that's pure poppycock. Anyone who says such a thing doesn't really know maps, or art.

"What is a work of art?" asked the British Sculptor Eric Gill, "A word made flesh," he answered "a thing seen, a thing known, the immeasurable translated into terms of the measurable." Maps fit the bill: the immeasurable and unknown translated through the work of the artist to the tangible and the understandable.

I was skiing alone through the Chamberlain Basin, deep in the central Idaho wilderness, a place I'd never been before. The maps--my portable art collection--in the top pocket of my pack took an unknown piece of land and made it understandable--and measurable. I knew how far I needed to ski to reach Chamberlain Creek and how much further it was from there to the ridge overlooking Big Creek, and from there how far it was to Yellow Pine, the remote backcountry town where I would fly back to civilization in two weeks.

All that was there and more. Art, particularly map art, is like a good book--illuminating, surprising, insightful, full of information--but it is a book written in another language, a language of symbols, lines and colors. It takes time to understand and appreciate that language, but once translated, its secrets are revealed: deep ravines, dark and cool in the summer's heat; intimate, marsh-fringed rivers just the right size for a canoe paddle; and skiable ridge spurs, safe and protected from the capriciousness of winter avalanches.

The day I entered Chamberlain Basin, the skies were lightly overcast. There were no shadows cast by the lodgepole. I had established a rhythm: poling, breathing, sliding the skis and poling, breathing, sliding . . . .

Then I came across something that stopped me: a set of ski tracks. I stood for several minutes in disbelief. I was alone, at least a hundred miles from the nearest plowed road and I had never expected to see anyone else. The fact be known, I had become quite smug for being there in the first place, but now I found that I had improbable company, that someone else was also traveling through the area--that is, until I realized the other person was me.

The thought came dimly at first, but then it became alarmingly apparent: I had skied in a long circle, perhaps several miles in circumference and come back on my own tracks.

* * *

I had read about others doing the same: arctic explorers, gold miners in Alaska and just plain everyday folk that had gotten lost. Old-timers, wise in the ways of the woods, will tell you that in the absence of directional landmarks, people tend to pull one direction and eventually circle back on themselves.

I never thought it would happen to me. The realization of it was both strangely fascinating and frightening. I was fascinated in this strange phenomenon of outdoor travel which causes a person to travel in a great arc, yet I was frightened as the gravity of my error began to set in. I had thought of myself experienced enough to be immune to these kinds of beginner's mistakes, but I wasn't. There was no one to help. I had to sort things out for myself, and if I didn't, I'd become just another one of those stories told by the old-timers.

Then I remembered my maps. I had forgotten them. I had been going by dead reckoning, traveling up the incline, letting the slope of the incline guide me, but the terrain had leveled sometime ago and I had traveled blithely along, believing that I was continuing in a straight line.

Even though I had maps, they weren't any use to me yet, I needed to know where I was first. I started skiing again, this time carefully sighting with my compass, moving from tree to tree, keeping on a straight line to the south. An hour past and then another and finally, I broke out of the timber and could look down across much of the basin.

I unfolded my maps and to keep them from being blown away in the wind, I weighed them down with ski poles and stuff bags of gear. The maps were now my most valuable possession, as important as the container of matches and fire starter carried in my pocket.

When one first looks at a map, particularly a topographic map, the kind that I carried with me in Chamberlain Basin, the lay of the land is initially hidden by the lithographic flourish of fine brown contour lines, but with time, the lines begin to make sense and landforms slowly emerge across the paper. As I looked at the map, I saw mountains rising from the concentric circles of brown and to my right in the distance, there they were, gray and distinct above the undulating basin. I saw a ridge taking shape from the v-shaped patterns on the map and out beyond where I knelt, there it was, its outline set against a darkening horizon. And, I could hear, at least I thought I could hear, the faint rushing of a stream to the south, appearing on the map as a thin blue line walled in by the brown U-shaped pattern of a valley. To see such things revealed on a map and find it standing life-like, nearby or in the distance, is a moving experience.

When one first looks at a map, particularly a topographic map, the kind that I carried with me in Chamberlain Basin, the lay of the land is initially hidden by the lithographic flourish of fine brown contour lines, but with time, the lines begin to make sense and landforms slowly emerge across the paper. As I looked at the map, I saw mountains rising from the concentric circles of brown and to my right in the distance, there they were, gray and distinct above the undulating basin. I saw a ridge taking shape from the v-shaped patterns on the map and out beyond where I knelt, there it was, its outline set against a darkening horizon. And, I could hear, at least I thought I could hear, the faint rushing of a stream to the south, appearing on the map as a thin blue line walled in by the brown U-shaped pattern of a valley. To see such things revealed on a map and find it standing life-like, nearby or in the distance, is a moving experience.

I was moved now--and moved to action. Once you know a couple of landmarks, you can find yourself quickly on a map. And once you find yourself, you know which way to go and how to go: my path led me downhill alongside a stream which drained into the big, wide-open meadows below.

By the time I reached the meadows, darkness had overtaken me, but the moonlight was so bright that I could find my way and I continued traveling. The meadows were long, made longer from my exhaustion from the long, long day. Half the night, it seemed, I skied across from one end of the meadow to the other.

But eventually I reached the far edge and there among blue shadows, I found an Idaho Fish and Game Cabin, the one shown on the map. It was unlocked, as is the custom for cabins left for the winter in large wilderness areas. I settled in the cabin, lit a candle, started a fire in the wood stove, and made a hasty dinner.

I rinsed out the cooking pot with some left-over warm water and slipped into my sleeping bag. Raising up on one arm, I watched the candle for a while and then as I started to blow it out, I hesitated. I reached over to the top pocket of my pack, I felt its contents from the outside. Through the thick nylon material, I could just make out the outline of folded paper. Reassured now that the maps were safe, I blew out the candle and fell into a sound sleep.

END

A Great Resource of Old Skiing Stories...

|

|

The book is truly a classic, one reviewer calling it the "standard by which other guidebooks are judged." Click here for more information on Winter Tales and Trails. . |

|

. Other Resources

The story about the Chamberlain Basin takes in Idaho's River of No Return Wilderness. One of the best books on the colorful history of the old-timers that lived along the river is Cort Conley's River of No Return. More Information.

A beautifully illustrated book is now available of the River of No Return country. Entitled Salmon River Country, the book is by award-winning photographer Mark Lisk and writer Stephen Stuebner. It's a colorful view of Salmon River Country and some of the hardy people who live and work along the river. More Information |

|