Reading from the Anthology of the Outdoor Experience

Edward Whymper (Scrambles Amongst the Alps)

Generation: Edward Whymper is from the Gilded Generation.

Historical Background

For centuries - at least in the West - mountains were hated and avoided. They were considered horrible places. The higher valleys were places of spirits and ghosts. In some areas, mountains were thought to be a punishment from the gods for human sins.

It is interesting to note that in the East (China, Nepal, & Tibet) mountains were not thought of this way. Instead, they were objects of wonder, worship and inspiration. They were not desirous from a climbing standpoint – although, certainly some in the East did climb to mountain summits - but rather they were something to be enjoyed.

The following poem nicely expresses the reverence held for mountains by Eastern cultures - and, in this, case it's an expression that almost embraces the mountain as one might a friend. It's by Chinese poet Li Po who lived in the 700's AD. (I particularly like this translation. I find it far more lyrical than the version most commonly found on the Internet.)

The flocks of birds have flown high and away,

A solitary drift of cloud, too, has gone wandering on.

And I sit alone with the Ching-t'ing Peak, towering beyond

We never get tired of each other; the mountain and I

- Li Po

Let’s go back the West. Between 1740 and 1790 changes of attitude were taking place in the West. People with the means started visiting remote villages, like Chamonix in France, just for the pleasure of viewing lofty mountains.

It was in the West, that some people started taking a great interest in reaching summits of great mountains, no matter what difficulties might be involved. One of the first major climbs in the Alps was Mt. Blanc. At approximately 15,800 feet, it is the highest in Europe and is located on the Italian and French border.

It was in the West, that some people started taking a great interest in reaching summits of great mountains, no matter what difficulties might be involved. One of the first major climbs in the Alps was Mt. Blanc. At approximately 15,800 feet, it is the highest in Europe and is located on the Italian and French border.

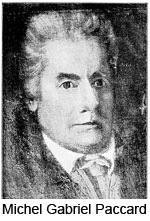

In the mid 1700’s, a wealthy scientist offered large reward to the first person to climb Mt Blanc. For over 20 years, many tried and failed. Finally in 1786, it was first climbed by a physician, Michel Gabriel Paccard and a peasant companion Jacques Balmat.

In the mid 1700’s, a wealthy scientist offered large reward to the first person to climb Mt Blanc. For over 20 years, many tried and failed. Finally in 1786, it was first climbed by a physician, Michel Gabriel Paccard and a peasant companion Jacques Balmat.

They were both French and lived in the Chamonix valley. To this day, the Chamonix area is an important center of mountaineering in the Alps.

In the 1800’s, the British began to take a great interest in mountaineering. British climbing in the Alps gradually increased, and by the mid and late 1800’s, dozens of new summits were attained. The “Golden Age of Mountaineering” is the term given to a particularly prolific period of climbing activity from 1854 to 1865.

In that decade, members of English Alpine Club climbed the most of difficult peaks in the Alps. To met the challenges, they developed tools and climbing methods. For example, they developed ice axes which are much the same as today’s ice axes.

The Golden Age came to an end in 1865 with the first ascent of the Matterhorn (14,782), the Alps last great summit.

The Golden Age came to an end in 1865 with the first ascent of the Matterhorn (14,782), the Alps last great summit.

The First Ascent of the Matterhorn

The First Ascent of the Matterhorn

Fifteen attempts had made on the Matterhorn. Whymper, himself, had made seven of those.

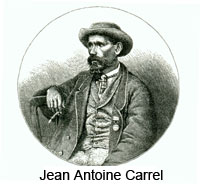

As the story in our reading unfolds, Edward Whymper finds himself in competition for the summit with Jean-Antoine Carrel. The two became antagonists.

Whymper learns that Jean-Antoine Carrel has double-crossed him and will be attempting to climb the mountain by the Italian Ridge.

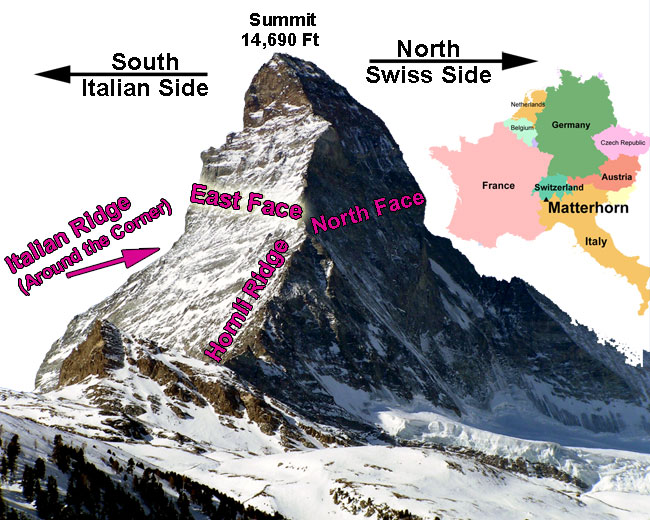

Whymper is alarmed. He quickly hikes over to Zermatt (on the Swiss side of the mountain) to line up climbers for an attempt on the Hornli Ridge.

When Whymper arrives in Zermatt, he finds that a Reverend Charles Hudson is there with a young companion named Hadow. With Hudson and Hadow is one of the best of the Chamonix guides Michel Croz. They are intent on making an ascent of the Matterhorn and believe, like Whymper that the Hornli Ridge offers them the best chances. Even better, Hudson is an experienced mountaineer; in fact, he is a better mountaineer than Whymper. Whymper has lucked out! He doesn't have to put together a party. There is a party of climbers ready to go.

When Whymper arrives in Zermatt, he finds that a Reverend Charles Hudson is there with a young companion named Hadow. With Hudson and Hadow is one of the best of the Chamonix guides Michel Croz. They are intent on making an ascent of the Matterhorn and believe, like Whymper that the Hornli Ridge offers them the best chances. Even better, Hudson is an experienced mountaineer; in fact, he is a better mountaineer than Whymper. Whymper has lucked out! He doesn't have to put together a party. There is a party of climbers ready to go.

Whymper also runs into Lord Francis Douglas. Douglas, a young man with some good climbs under his belt, has employed the guide Peter Taugwalder who has been exploring the Hornli Ridge.

All of them Whymper, Hudson, Hadow, Croz, Douglas and Taugwalder combine forces for the climb. (Taugwalder son would also join the party.)

As it turns out, the Hornli Ridge was an excellent route, and Whymper’s party reached the summit.

The following illustration shows the location of the Matterhorn on the Swiss-Italian border. It also shows Whymper's route (Hornli Ridge) and Carrel's route (Italian Ridge):

One of the scenes described by Whymper in his narrative is where he and Croz throw rocks down mountain to make the Italian climbers aware that his party made it to the top first. Whymper speculates that the Italians must think there are "spirits" on the mountain. Jean-Antoine Carrel would disagree with that. He knew he had been beaten by Whymper. "It was Whymper," he told a friend, "I recognized him by his white trousers."

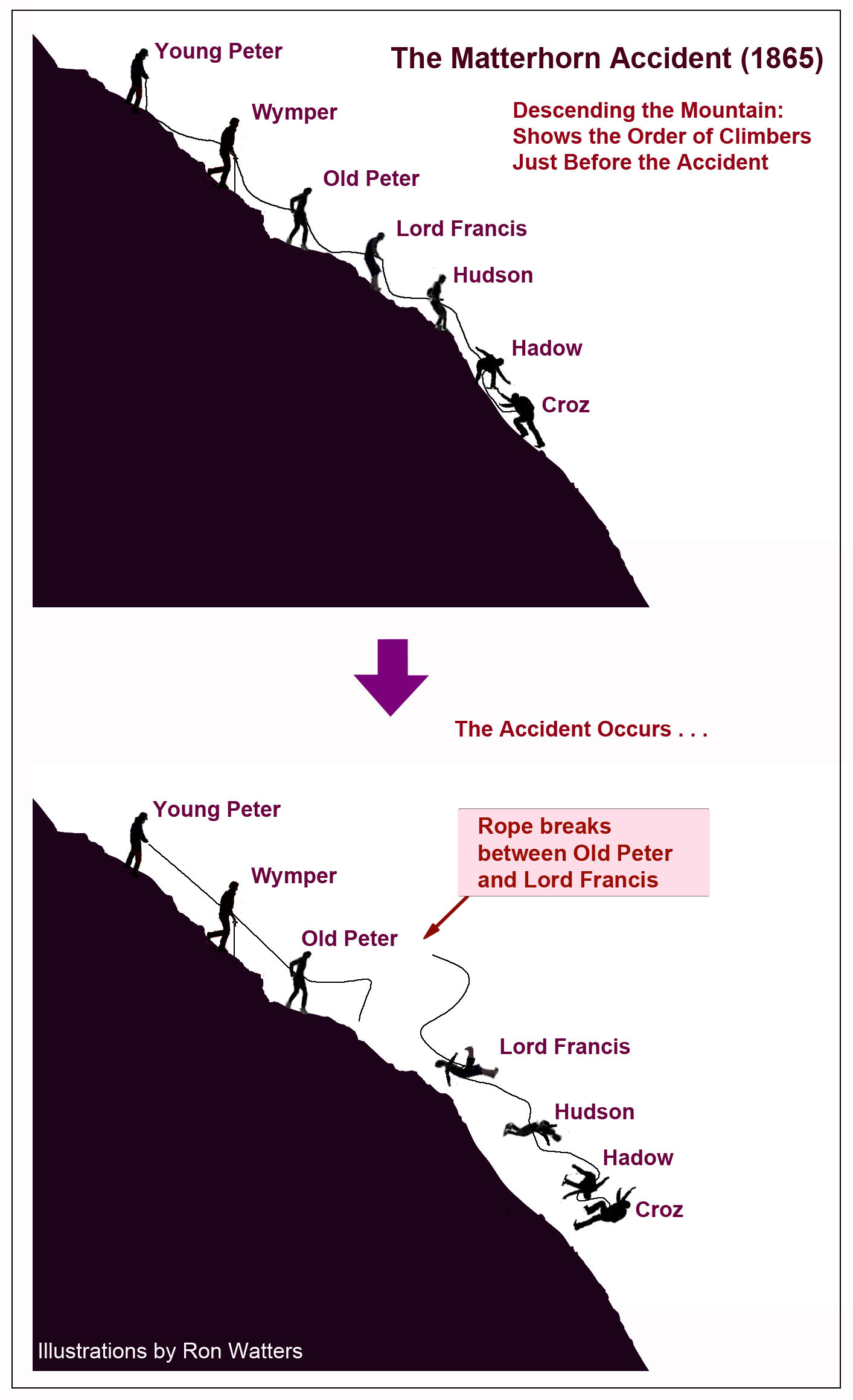

Here’s the order of the descent:

Croz was helping Hadow. Hadow slid and fell against Croz. The chain reaction started. Old Peter, Whymper, and Young Peter braced themselves, but the rope broke between Old Peter and Lord Francis (see illustration below). All the four men fell to their deaths.

The Taugwalders were terrified and in shock after the accident. Eventually Whymper had to help them down.

The Taugwalders were terrified and in shock after the accident. Eventually Whymper had to help them down.

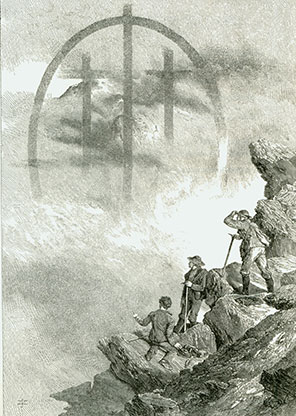

On the way down, about 6 pm, they saw something that caused them to pause. It was an atmospheric condition, quite rare, where light is refracted in the mist.

They observed something like a white rainbow consisting of an arch and two crosses. This type of condition is called a “fog bow.”

In his narrative, Whymper points out that “fog bow” is a term that was used by the explorer Sir William Edward Perry.

We also looked at several other atmospheric conditions including the following:

Brocken spectre The sun is behind an individual, and their greatly enlarged shadow appears in a cloud or mist.

Brocken spectre The sun is behind an individual, and their greatly enlarged shadow appears in a cloud or mist.

(Photo Credit: Dmitry Shapovalov)

Sun Dogs – Light reflecting off of small snow crystals (sometimes called diamond dust). Usually sun dogs are most prominent when the sun is low in the horizon.

Sun Dogs – Light reflecting off of small snow crystals (sometimes called diamond dust). Usually sun dogs are most prominent when the sun is low in the horizon.

(Photo Credit: Joseph N Hall)

Crepuscular Rays – Light from the sun streaks through gaps in the clouds and is scattered by dust in the air.

Crepuscular Rays – Light from the sun streaks through gaps in the clouds and is scattered by dust in the air.

(Photo Credit: Ron Watters)

After the Accident

Afterwards, enormous publicity was given to the accident in Britain. The press was united in their criticism of mountaineering. The Queen (Queen Victoria) even asked her advisers if laws could be passed to prevent climbing and mountaineering.

But it didn't stop mountaineering. In fact, it made it even more attractive. Since most of the great summits of the Alps had been climbed, mountaineers began looking elsewhere. Whymper went on to climb in Central and South America and the Canadian Rockies.

Whymper was young climber, known only to a small circle of mountaineers, but after the tragedy, and after his book was published, he became a world celebrity. He was the first climber that was able to live by writings and lectures. In later life, however, he became an alcoholic. Perhaps he never got over the terrible tragedy on the Matterhorn. He continued to climb but as he aged he become more and more a joke to younger, up-and-coming climbers. He died in 1911 at the age of 71 and is buried in Chamonix.

Peter Taugwalder (Old Peter) suffered from Matterhorn experience. Although he had tried to stop the fall, rumor spread that he had cut the rope to save himself (or that he ensured he was on the weakest rope). The suspicions were unfounded, but they drove him away from his valley near Zermatt to the United States were he lived for several years.

Jean-Antoine Carrell was defeated, but he was not discouraged. Only three days after Whymper's ascent, he reached the summit of the Matterhorn, climbing it by the Italian ridge. For that day and age, it was a cutting edge climb. The final section of the Italian Ridge is more difficult than anything on the Hornli route. Interesting enough, any animosity between the Carrell and Whymper was forgotten, and 14 years later, the two of them were climbing together and putting up first ascents in South America.

We’ll come back to mountaineering when we look at mountaineering's ultimate challenge and its greatest prize: the summit of the highest peak in the world Mt. Everest.

Pub History: This page was originally located at the following URL:

https://www.isu.edu/~wattron/OLNotes5.html

[End]