.

Isabella Bird’s A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains

AND

John Muir’s Steep Trails

Generations: Isabella Bird and John Muir are from the Gilded Generation.

Lecture Notes on Isabella Bird’s A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains

Background on Isabella Bird

In 1854 at the age of 22 years, Isabella Bird was in ill health and was bothered by a spinal disorder. A doctor suggested fresh air, perhaps an ocean voyage. So in 1854, she sailed across the ocean to Canada, then traveled to Eastern and Midwestern US. The illness was nearly forgotten.

In 1854 at the age of 22 years, Isabella Bird was in ill health and was bothered by a spinal disorder. A doctor suggested fresh air, perhaps an ocean voyage. So in 1854, she sailed across the ocean to Canada, then traveled to Eastern and Midwestern US. The illness was nearly forgotten.

The mid to late 1800s was a time when most women didn't travel unescorted. Yet when Bird traveled, she travelled without company. She found that she liked traveling alone, but she was also a social creature and enjoyed meeting and staying with others.

Two years after she returned from her North American trip, she published her first book: The Englishwoman in American (1856).

She traveled most of her life, returning to Canada and the Eastern US several more times. Just before her western US trip (a trip that she took in 1873 and described in a Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains), Bird spent several months in Hawaii. After her western trip, she went to Japan. Other countries she visited include Persia, Tibet, Korea and China.

A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains

A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains

Our readings come from Isabella Bird's book A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains.

The book, published in 1879, sold quite well. Her English compatriots were hungry for books about America and the American West, and A Lady's Life and her other books kept them nourished and entertained. (Wymper did the illustrations)

In A Lady's Life, Bird uses letters as her literary form. So far we've had the following:

- Journal/diary for Journal of a Trapper

- Autobiography & Essay for Walden

- Humor for Roughing It

- Narrative for Scrambles Amongst the Alps

- Biography for Beyond the 100th Meridian

- Journal for The Exploration of the Colorado

Let's look at the events leading up to her arrival at Estes Park . . .

She begins her western journey in California and takes the Transcontinental Railroad to the east, pausing in Truckee, California. She wants to see Lake Tahoe. That night she stays in a pigpen of a room with no windows, and her sleep is broken by gunshots coming from the outside.

Nevertheless, the next day she is up and ready to find her way to Lake Tahoe. She locates a stable, rents a horse, and starts riding. The surrounding country is still very much wilderness, and a bear appears, scares her horse, and throws her. The horse runs back to Truckee, leaving her on the trail. With her horse gone, she has no other choice but to turn around and walk all the way back to Truckee.

Nevertheless, the next day she is up and ready to find her way to Lake Tahoe. She locates a stable, rents a horse, and starts riding. The surrounding country is still very much wilderness, and a bear appears, scares her horse, and throws her. The horse runs back to Truckee, leaving her on the trail. With her horse gone, she has no other choice but to turn around and walk all the way back to Truckee.

The way that she treats this incident tells us something about her intrepid nature. Even though she wasn’t able to reach her destination, she laughs it off and makes a correction in her plans. Rather than thinking of it as a failure, the experience becomes a part of the adventure.

Upon returning to Truckee, she continues the journey, taking the train to Cheyenne, Wyoming. She relates how Cheyenne is an important supply point for the regional area. In town are freight wagons hauled by four to six horses and even larger wagons hitched with teams of oxen. At times there are as many as 100 wagons crowded into Cheyenne.

She then takes a spur line to Greeley, Colorado. She describes the ride thusly: "An American railway car, hot, stuffy and full of chewing, spitting Yankees, was not an ideal way of approaching the range."

In Greeley, she spends the night at a rooming house, but it is very small, has canvas partitions separating rooms, and is "thick with black flies." She tries to sleep, but insects are crawling on her, and she finally rises, sits in a chair, and sleeps while seated.

The next day, she catches a ride on a wagon to Fort Collins. It’s a boiling hot day, and she gets ill. In Fort Collins, she obtains a room, but it’s full of flies. That night she eats a dinner of beef as tough as shoe leather covered in oily butter and drowned flies.

In the morning, she leaves Fort Collins in a buggy driven by a "profoundly melancholy young man." She is trying to get to Estes Park, but everything is conspiring against her. She heads up into the foothills of the Rockies where she's heard that there are some families that provide rooms for travelers, but her buggy driver gets lost. Finally they come across a broken down farm where she able find lodging for $5 a week.

Bird is not so sure she wants to stay there, but she doesn't want to go back to Fort Collins which will take her away from the mountains. She also doesn't want to go to Denver since she’s not interested in the city. Nor does she want to travel back to the railroad and continue her journey east. She wants to get to Estes Park.

Her hosts at the farm are not very welcoming: "Here life is rough,” she writes, “rougher than any I had ever seen, and the people repel me by their faces and manners."

She decides to tough it out for a few days and see if she can find some way of getting to her destination. Eventually, she talks the husband into guiding her to Estes Park. Alas, he doesn't know the way and they get lost and have to come back.

Finally, she meets some neighbors (Dr. and Mrs. Holland). The doctor takes over and makes arrangements for her to travel to Longmont (a nearby town and on the route to Estes Park). There she is outfitted with a horse. Two teenagers whom she refers to as the "students" guide her successfully to Estes Park.

Our reading starts when she has arrived in Estes Park.

Below is a map showing Isabella travels in Colorado. Her route is indicated by a red dotted line.

Women and Mountaineering

Isabella Bird was an adventure traveler, not a mountaineer. Nonetheless, there were energetic and adventurous female climbers from the gilded generation. They didn’t, however, have it easy. During this period of history, it was scandalous for women to wear trousers or even skirts that might show a bit of ankle. And . . . were they really spending time camping in the mountains with men? – men they might not be married to? Utterly reprehensible!

Isabella Bird was an adventure traveler, not a mountaineer. Nonetheless, there were energetic and adventurous female climbers from the gilded generation. They didn’t, however, have it easy. During this period of history, it was scandalous for women to wear trousers or even skirts that might show a bit of ankle. And . . . were they really spending time camping in the mountains with men? – men they might not be married to? Utterly reprehensible!

Nonetheless, despite societal strictures, women climbed. You may remember that Mt. Blanc was first climbed 1786 by Michel-Gabriel Paccard and Jacques Balmat. The first woman to climb it was Marie Paradis in 1808.

We also know that Edward Whymper’s first ascent of the Matterhorn was in 1865.

We also know that Edward Whymper’s first ascent of the Matterhorn was in 1865.

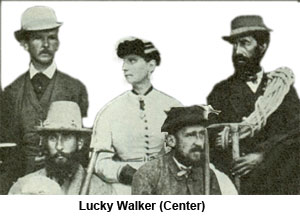

It was climbed just 6 years later by a woman, Lucy Walker, from England.

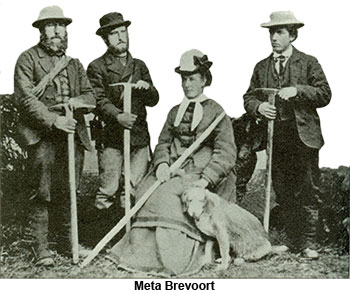

She beat out American Meta Brevoort who made the summit two weeks later.

Meta Brevoort was a prolific climber, going on to make a number a significant climbs over the next few years.

Meta Brevoort was a prolific climber, going on to make a number a significant climbs over the next few years.

The third ascent of the Matterhorn by a woman occurred in 1895. It was climbed by Annie Smith Peck, an American, who had the temerity to do the ascent in woolen knickers.

The first woman to climb Longs Peak was Addie Alexander. She climbed the mountain in 1871, just three years after the first ascent of the mountain by John Wesley Powell's party. Two years later, in 1873, it was climbed by Anna Dickinson. Isabella Bird's ascent later the fall of 1873 is often referred to as the third ascent by a woman, though it may have been fourth since a least one source names a "Miss Bartlett" climbing it in 1871.

One notable historic female climber is Fanny Bullock Workman. She, along with her husband, made a 3,000-mile bicycle journey across Spain in 1895. Dressed in the style of the time, Fanny rode in a long skirt. She passed through the countryside with her trademark tea kettle swinging back and forth from her handlebars.

One notable historic female climber is Fanny Bullock Workman. She, along with her husband, made a 3,000-mile bicycle journey across Spain in 1895. Dressed in the style of the time, Fanny rode in a long skirt. She passed through the countryside with her trademark tea kettle swinging back and forth from her handlebars.

She did eight Himalayan expeditions between 1898 and 1912. At 47 years of age, Workman set a women's world climbing record in 1906 when she scaled 22,815-foot Pinnacle Peak in Kashmir. She subsequently climbed even higher, reaching the summit of 23,300-foot Nun Kun peak.

Workman climbed with men, but women did organize their own expeditions. The first all women's expedition to Himalayas occurred in 1955 and is described in the book Tents in the Clouds.

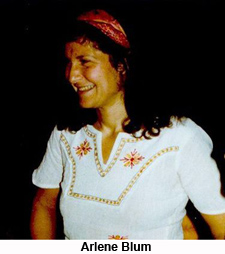

Back in North America, Arlene Blum wanted to climb Denali (Mt McKinley) in Alaska, but she was told by a guiding company that women could only go as far as base camp. Upon hearing that, she told the company to take a flying leap and organized her own Denali expedition consisting of all women. Her party successfully climbed the mountain in 1970.

Back in North America, Arlene Blum wanted to climb Denali (Mt McKinley) in Alaska, but she was told by a guiding company that women could only go as far as base camp. Upon hearing that, she told the company to take a flying leap and organized her own Denali expedition consisting of all women. Her party successfully climbed the mountain in 1970.

She followed up by organizing an all-women’s expedition to Annapurna in 1978. To raise money, t-shirts were sold with the slogan: "A women's place is on top." The expedition successfully put the first woman (and first American) on top of Annapurna, but it was marred by tragedy. Two woman died in accidents. Among the world's big mountains, Annapurna is the most deadly. As of March 2012, there have been 191 successful ascents, but 52 deaths during ascents and nine deaths upon descent. That's a ratio of 34 deaths per 100 safe returns.

The first female ascent of Mount Everest was accomplished by Junko Tabei from Japan who climbed it in 1975 on an all-women's team.

Lecture Notes on John Muir’s Steep Trails

John Muir is from the Gilded Generation

Background on John Muir

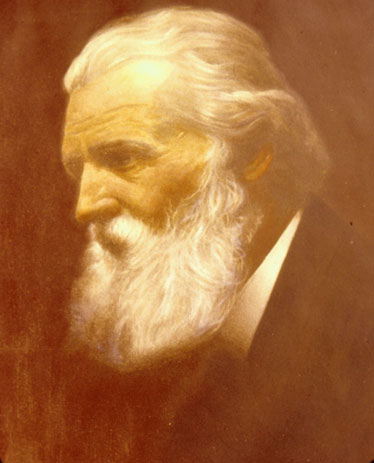

Muir was born in Scotland. His family moved to America when he was 11, homesteading a farm in Wisconsin. His father was very religious and held the traditional view that God was found in the bible and one communed with the divine by attending church and reading scripture. He wasn't a transcendentalist. Nature played no role in his religion.

Muir was born in Scotland. His family moved to America when he was 11, homesteading a farm in Wisconsin. His father was very religious and held the traditional view that God was found in the bible and one communed with the divine by attending church and reading scripture. He wasn't a transcendentalist. Nature played no role in his religion.

Muir possessed a creative mind and was gifted inventor. After he left his father’s farm, he could have become a rich man, but his life led him elsewhere. He spent time at the University of Wisconsin. There he immersed himself in biology and geology courses. But he also found literature fascinating, and, in particular, found kindred spirits in Emerson, Thoreau and the other transcendentalists. The transcendentalists spoke to him. Unlike his father’s belief, he came to understand that there was a connection between nature and God, and, fact, nature to him was the direct link to God.

In March of 1867, while working in Indiana, a file flipped up and pierced his eye. Fluid from the eye leaked out on his hand. He was blinded in that eye, and, in a sympathetic reaction, the other eye became blinded. For nearly a month he lived in darkness.

During those disquieting days, he decided he wasn't going to waste any more of his life. If his sight returned, he would head out and see the wonders of nature. Miraculously, his eyesight did returned, and he quickly made new plans for the future. "God has to nearly kill us sometimes to teach us lessons," he wrote later of his experience.

He began his new life by taking a walking trip, a 1,000 mile trip, from Indiana to Gulf of Mexico.

For Muir, transcendentalism became the way in which he interpreted his relationship with the outdoors and wild country. As he walked, he carried a volume of Emerson's essays. Muir's ideas, expressed in his later writings, became variations of the transcendental philosophy.

After his trip to Gulf of Mexico, he traveled by ship to San Francisco arriving there in 1868. He was 31 years old. He stopped one of the first people he met and asked for the best way out of town.

"But where do you want to go?" the man asked him.

John Muir famously replied: “To any place that is wild."

Where he wanted to go was Yosemite, and he set out that direction by foot. It was April and the flowers were blooming: "All the air was quivering with the songs of the meadow larks," he wrote.

He climbed a low pass (Pacheco Pass) over looking the Central Valley and described it this way:

"A landscape was displayed that after all my wanderings still appears as the most beautiful I have ever beheld. At my feet lay the Great Central Valley of California, level and flowery, like a lake of pure sunshine, forty or fifty miles wide, five hundred miles long, one rich furred garden of yellow composite. And from the eastern boundary of this golden flower bed rose the mighty Sierra, miles in height and so gloriously colored and so radiant.”

“Then it seemed to me that the Sierra should be called, not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light. And after ten years of wandering and wondering in the heart of it, rejoicing in its glorious floods of light, the white beams of the morning streaming through the passes, the noonday radiance on the crystal rocks, the flush of the alpenglow, the irised spray of countless waterfalls, it still seems above all others the Range of Light.”

So he walked across the central valley heading to his "Range of Light," across miles and miles of wildflowers. The sights and sweet smells of flowers overwhelmed his senses. At night he would lie down, and in the morning when he awoke, he found himself surrounded by flowers.

Muir had found home. He stayed in California – spending months in the Sierras, particularly in the Yosemite area.

Muir had found home. He stayed in California – spending months in the Sierras, particularly in the Yosemite area.

In May of 1871, Muir’s college professor learned that Ralph Waldo Emerson was coming to California and helped arrange an introduction for Muir. Emerson found Muir fascinating. Although, Emerson didn't take Muir up on his offer to go on a month camping trip through the Sierra, the two men continued their contact through letters.

Later Emerson would include Muir on his list of the most influential men in his life.

In 1872, the year after Emerson had visited, Muir began publishing articles. In the late 1890’s and early 1900’s he published a number of books. In 1892, he helped found the Sierra Club in an effort to protect wild areas which held such a great importance in his life. In 1903, Theodore Roosevelt spent time with Muir in Yosemite, and Muir was able to convince Roosevelt that Yosemite's valley floor needed federal protection.

Muir died in 1914, but his legacy is long-lived. His prolific pen and his activism helped save such American treasures as Yosemite National Park, and he is truly one of the great wilderness figures of all time.

[End]